Bob Whaley and the Best Evidence Rule

Prosecutors are quite jealous about their won/loss records, and that makes them leery of trying certain cases with dubious facts, sympathetic defendants, or talented defense lawyers. When my father, Robert Whaley, was a prosecutor for Dallas County, Texas, in the 1970s, he was afraid of nothing, but even he was dubious about what I shall call the “Smith” case, which none of the other prosecutors wanted to touch since all these elements combined to shout the words “Not Guilty” as the likely outcome. Ms. Smith was charged with Driving While Intoxicated (“D.W.I”) and Charles Tessmer was her defense attorney.

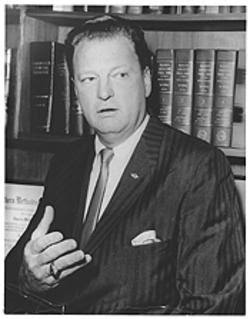

Prosecutors are quite jealous about their won/loss records, and that makes them leery of trying certain cases with dubious facts, sympathetic defendants, or talented defense lawyers. When my father, Robert Whaley, was a prosecutor for Dallas County, Texas, in the 1970s, he was afraid of nothing, but even he was dubious about what I shall call the “Smith” case, which none of the other prosecutors wanted to touch since all these elements combined to shout the words “Not Guilty” as the likely outcome. Ms. Smith was charged with Driving While Intoxicated (“D.W.I”) and Charles Tessmer was her defense attorney.Charles Tessmer (see photo) is known today as one of the greatest criminal defense attorneys in the history of the country. He tried over 1,000 cases, represented more than 175 people facing death but never had one executed, and has also done a great deal of appellate work, including three cases before the United States Supreme Court, winning two. His resume includes being past President of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, author, producer, and director of the film “The Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald” (Tessmer once declined to represent Jack Ruby, Oswald’s assassin), and induction into the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Hall of Fame in 1998.

He often drove the Dallas D.A.’s Office nuts with his brilliant defense work in D.W.I. cases. Particularly when the defendant’s level of intoxication was only slightly over the legal limit would Tessmer become a legal wizard at talking the jury into letting his client go free. “Ever have a drink yourself,” he’d rhetorically ask the jury, “and then, knowing it was just one drink, feel it was okay for you to drive?” The Smith case had Tessmer’s favorite fact: a woman who was barely legally drunk, just a smidgeon over the limit.

Around the same time, Dad was the prosecutor of a different D.W.I. case that Tessmer was defending, but Dad wasn’t worried about this one. Tessmer’s client had been very drunk and had nearly caused a serious accident. To prove how drunk the man was, Dad put a breathalyzer expert on the witness stand and asked introductory questions designed to establish the witness’s qualifications. “Did you graduate from a school where you learned how to operate the breathalyzer?” Before the witness could answer, Tessmer called out, “Objection!” Dad turned to him with a smile. “This will be interesting,” he commented to Tessmer. “What could possibly be objectionable about that question?” Tessmer’s answer: “The Best Evidence Rule—he can’t testify to what his diploma says!” The judge didn’t hesitate. “Sustained,” he ruled. “Your Honor!” Dad protested.

A little bit of the law of evidence here. The Best Evidence rule is simple. It states that you can’t testify to what is written on a piece paper. The paper itself is the “best evidence” of what it says, so it should be marked as an exhibit and introduced into the proceedings that way. The rule is designed to apply to letters and documents, but certainly has nothing to do with graduation from school, and no one who understands the rule would think so. But, as I tell my law students (learning this from my own bitter experiences in the courtroom), no matter how wrong, silly, or stupid, the law is what the trial court judge thinks it is, and if you can’t afford to appeal, you have to work with it.

Outraged, Dad asked the judge for a ten minute recess so he could run to the library and grab a few references to show the judge he was wrong, but His Honor simply remarked, “Move along, Mr. Whaley.”

How Dad got the breathalyzer test evidence finally admitted I don’t remember being told, but there are various ways of doing that (including, as a last resort, producing the diploma). Finally learning how very drunk the man had been, the jury duly convicted, and that prosecution was over. But it got Dad to thinking about the Smith case. Once again Tessmer would be the defense counsel, and, by coincidence, it was to be tried before the learning-impaired judge just mentioned. Pondering, Dad went back to the office, picked up the file, and suddenly told everyone, “I’m going to take this one.” They looked at him suspiciously. What was Whaley up to now?

Comes the date of the trial. Tessmer is there with his client, the woman whose alcohol level had been minimal, and at this moment Dad is concluding the case for the prosecution. The jury had already heard testimony from the police that Tessmer’s client had been weaving all over the road before being pulled over, and that she smelled of alcohol on her breath while slurring her words. Dad put the breathalyzer expert on the witness stand, and asked him if he’d graduated from a school that had taught him how to use the machine.

“My heart was beating hard,” Dad later told me. “I was worried that Charlie wouldn’t object, and if that happened, well . . . .” But Tessmer did object, almost as if bored, citing the best evidence rule. “Sustained,” the judge immediately ruled. Dad paused, very pleased. “No further questions,” Dad announced. “The prosecution rests.” He sat down as Tessmer leaped to his feet. “WHAT!” he protested. Dad smiled. Due to the judge’s ruling, the evidence demonstrating that the defendant was only slightly drunk had not gotten into the record. Tessmer stood there, stung, thinking hard. After a bit, he concluded there was nothing he could do. He couldn’t call the defendant to testify she was only a little bit drunk—who would believe that? Nor could he call the breathalyzer expert back to the stand and lamely try to get in the evidence he’d just objected to (with Dad, the Best Evidence Rule now his friend, ready to pounce) . Finally, Tessmer could only manage, “The defense rests.”

When some of you reading this blog (see “Bob Whaley, Boy Lawyer” March 28) asked more examples about my father not playing by the usual rules in the courtroom, this story came to mind. Taking advantage of the other side’s deliberate misuse of the Best Evidence Rule led a jury to convict a woman Charles Tessmer had undoubtedly thought would be walking out of the courtroom with him at the end of the day.

It would be my guess that he never again mentioned the Best Evidence rule in a court of law.

________________________________________

Related Posts:

“My Competitive Parents,” January 20, 2010

"Goodbye to St. Paddy's Day," March 2, 2010

“Bob Whaley, Boy Lawyer,” March 28, 2010

"My Mother's Sense of Humor," April 4, 2010

“The Sayings of Robert Whaley,” May 13, 2010

“Bob and Kink Get Married,” June 2, 2010

“Dad and the Cop Killer,” July 19, 2010

“No Pennies In My Pocket,” July 30, 2010

“Doug, Please Get My Clubs From the Trunk,” August 20, 2010

“The Death of Robert Whaley,” September 7, 2010

"My Missing Grandmother," December 26, 2010

"Bob Whaley Trapped in Panama," January 21, 2011

"The Death of My Mother," March 31, 2011

"Life's Little (But Important) Rules," April 23, 2010

“A Guide to the Best of My Blog,” April 29, 2013

Great Story!

ReplyDelete